📖 Every Chapter of Thinking Fast, and Slow in 7 Minutes

Jul 31, 2018 • 7 min • Reading

About a week ago, I finally finished reading Thinking, Fast and Slow by Daniel Kahneman. While released in 2011, the bestseller remains just as applicable today as it was nearly eight years ago.

This is for good reason; leave it to a Nobel Prize winner to take complex concepts on psychology and the inner-workings of the mind, making them accessible to anyone through practical application and examples.

I have already seen some things that I learned from the book begin to change the way that I make decisions and deal with bias. You would be surprised how little control we truly have over our day-to-day thought process.

While not the quickest read, clocking in at nearly 600 pages, I can look back and be happy that I took on the endeavor. Furthermore, I thought it would be cool to share what I learned in a simple and concise way.

The results of which are located below, broken down with one sentence dedicated to each of the 38 chapters in Thinking, Fast and Slow.

Keep in mind that there’s a lot more to the book than I could ever communicate in one concise post, so I highly recommend checking out the masterpiece itself if any of these concepts seem interesting to you.

Part I: The Two Systems

1. The Characters of a Story

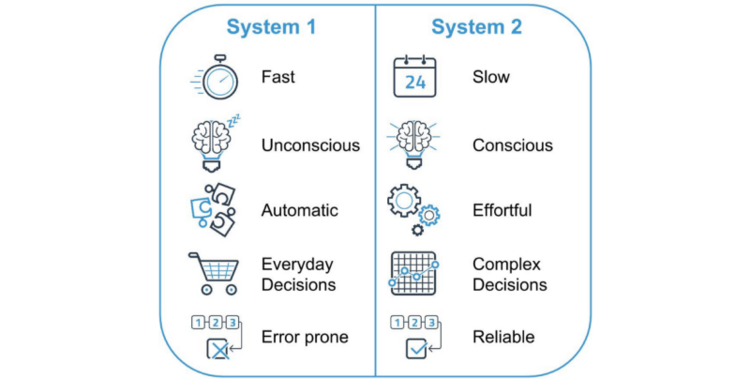

We have two primary systems for thinking; System 1 operates quickly with no sense of voluntary control, while System 2 deals with effortful mental activity of any kind.

2. Attention and Effort

We avoid cognitive overload by breaking up current tasks into small steps to be committed to long term memory; we are naturally drawn to solutions that use as little mental effort as possible.

3. The Lazy Controller

One of the main functions of System 2 is to monitor and control suggestions from System 1, however it is often lazy and places too much faith in intuition.

4. The Associative Machine

System 1 provides impressions that often turn into beliefs and actions; even the most insignificant of ideas can trigger other ideas and so on.

5. Cognitive Ease

You act differently when experiencing cognitive ease vs. strain; you’ll probably make less errors when strained, but you won’t be as creative.

6. Norms, Surprises, and Causes

The main function of System 1 is to maintain and update a model of your personal world, which represents what is normal in it.

7. A Machine for Jumping to Conclusions

System 1 is radically insensitive to both the quality and the quantity of the information that gives rise to impressions and intuitions.

8. How Judgements Happen

When making judgements, we often either compute much more information than we need, or we attempt to match the underlying scale of intensity across dimensions.

9. Answering an Easier Questions

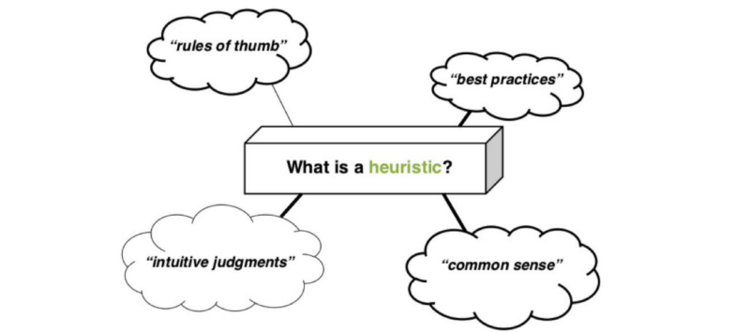

If a satisfactory answer to a hard question is not found quickly, System 1 will find a related question that is easier and answer it instead.

Part II: Heuristics and Biases

10. The Law of Small Numbers

We have a strong bias towards believing that small samples closely resemble the population from which they are drawn.

11. Anchors

The anchoring effect occurs when a particular value for an unknown quantity influences your estimate of that quantity.

12. The Science of Availability

The ease with which we can think of examples is often used to judge the frequency of events.

13. Availability, Emotion, and Risk

We try to simplify our lives by creating a world that is much tidier than reality; in the real world, we often face painful tradeoffs between benefits and costs.

14. Tom W’s Specialty

It’s common practice to overweight evidence and underweight base rates; how do you know that your case is different?

15. Linda: Less Is More

Adding detail to scenarios makes them more persuasive, but less likely to come true.

16. Causes Trump Statistics

You’re more likely learn something from an individual case or example than you are from facts and statistics.

17. Regression to the Mean

It’s important to understand the natural fluctuations of quantifiable performance.

18. Taming Intuitive Predictions

In order to produce unbiased predictions, start with the average and systematically move from there based on matching and estimated correlation of evidence.

Part III: Overconfidence

19. The Illusion of Understanding

We believe that we understand the past due to our constantly adjusting view of the world; this implies that the future should be knowable as well, however we understand the past less than we think.

20. The Illusion of Validity

Subjective confidence isn’t a reasoned evaluation that a judgment is correct, but rather a feeling that reflects the coherence of information and the ease of processing it.

21. Intuitions vs. Formulas

Whenever you can replace intuition and impressions with a structured, yet simple formula, you should at least consider it.

22. Expert Intuition: When Can We Trust It?

Under normal conditions, you can usually trust an expert’s intuition, however when dealing with less regular environments, be more skeptical.

23. The Outside View

We have a tendency to plan projects based on best-case scenarios and without taking into account all of the previous similar cases out there.

24. The Engine of Capitalism

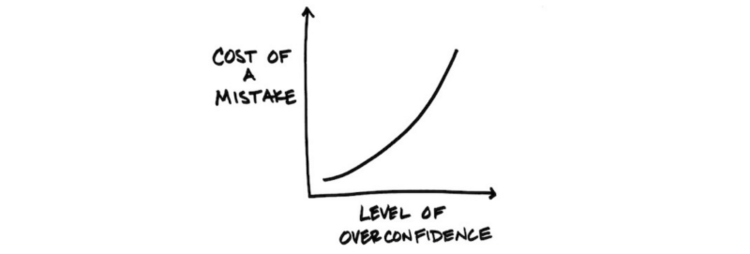

The suppression of doubt contributes of overconfidence; try using a pre-mortem to legitimize your doubts.

Part IV: Choices

25. Bernoulli’s Errors

Bernoulli’s expected utility model lacks the idea of a reference point, the value of something is largely dependent on a person’s current situation.

26. Prospect Theory

In mixed gambles, we are naturally risk-averse; while for bad choices, when a sure loss is guaranteed, we are more likely to seek out risk.

27. The Endowment Effect

We naturally assign more value to things just because we own them.

28. Bad Events

We generally work harder to avoid losses than we do to secure gains.

29. The Fourfold Pattern

Humans are just as risk seeking in the domain of losses as we are risk averse in the domain of gains.

30. Rare Events

People often overestimate the probabilities of unlikely events; this causes us to overweight them in our decisions.

31. Risk Policies

In order to avoid exaggerated caution induced by loss aversion, take a broad frame; think as if the decision is just one of many.

32. Keeping Score

Rewards and punishments shape our preferences and motivate our actions, all kept track of by difference mental accounts.

33. Reversals

Single evaluations call upon the emotional responses of System 1, whereas comparisons involve more careful assessment, typically by System 2.

34. Frames and Reality

Logically different statements can evoke different reactions depending on how they are framed.

Part V: Two Selves

35. Two Selves

We have an experiencing self and a remembering self; the latter of which keeps score and governs what we learn in order to make decisions.

36. Life as a Story

Most people are indifferent to their experiencing self, only caring about the memories collected in order to fuel different narratives.

37. Experienced Well-Being

People’s evaluations of their lives and their actual experience are related, but different.

38. Thinking About Life

The word happiness doesn’t have a simple meaning and should not be used as if it does.

Wrapping Up

Upon some reflection, I realized there was a lot of wisdom packed in the pages of Thinking, Fast and Slow. Far too much wisdom to pack into one sentence per chapter. However, I hope this may provide you with an effective appetizer to the entree that is the novel itself.

Lastly, I’m excited to actively try and incorporate these insights and concepts into my everyday life in order to make more sound, mindful, and unbiased decisions. I would be remiss if I didn’t call upon you to do the same.

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this post and you’re feeling generous, perhaps follow me on Twitter. You can also subscribe in the form below to get future posts like this one straight to your inbox. 🔥